We’re still on the subject of doing many things at a time,

or over a lifetime, which we started with in the last post. Like I said, there

are a couple of books which address this very topic in detail. The first of

these is What Do I Do When I Want To Do

Everything? by Barbara Sher, sub-titled “A leading life coach’s guide to

creating a life you’ll love”. Barbara’s main plank is that people who like to

keep trying new things, never settling down to one vocation, much to the

frustration of their families and well-wishers, may be just made to be learners

throughout their lives. She calls them (us!) “Scanners” (I will use the word always

with a capital S, to give it a proper weight and dignity, like President or

Comptroller).

Apparently it is the process of taking up a subject or field

of activity and studying it deeply enough to be competent in it, that motivates

Scanners. I think I meant something like this in a previous post (#37 To find a

purpose) when I talked about making the process itself interesting so that one

is not too involved in the results. For Scanners tend to leave the subject when

once they have achieved a certain level of familiarity; they are not in the

game of doing the same thing over and over again as a job… sounds familiar!

Sher has a detailed typology of Scanners: we can be Serial

Masters, who like to take up one thing at a time, master it, and then abandon

it; or Cyclical Scanners, who tend to circle back to older interests over a

period of years (my front burner - back burner idea makes me this type, I

guess). Others are Samplers, who like to try a number (dozens) of things,

without going too deep into many of them. Whatever type you are, Sher’s message

is that it’s alright to be like that, even if you don’t get to leave behind a

legacy in any of them.

One of the most useful (if that can be said of any Scanner

activity!) is the idea of keeping a Scanner Daybook, to record all your

fleeting inspirations and ideas every day by the hour. The way the author

describes it, it is meant to be a sufficiently heavy and impressive looking

tome, preferably well upholstered and fit to display on its own stand (like an

illuminated bible or domesday book or something!), with large unlined pages to

receive your thoughts, compositions, drawings, recipes, samples and

memorabilia, like da Vinci’s notebooks. I gather that the idea of the Daybook

is to use one pair of open pages for each idea or project that occurs to you,

and keep on opening new pages as each new idea strikes your mind. Over time, it

is supposed to end up as a complete store of all your ideas, even if you

haven’t acrtually worked through any or most of them. As you add detail or

achieve progress, I guess you are expected to fill in notes in the two-page

spread over the years.

I have to confess that this may be a bit beyond my

persistance and work habits, although the idea sounds good. I have so far used

a series of discarded diaries for my note taking, using separate ones for my

work-work activities (mainly the light-weight, flexible, spiral-bound notebooks

they hand out in seminars and training courses), which last up to a month each,

and a separate series for my project ideas, for which I use the out-of-date

hard-bound diaries that accumulate all the time (of course, they have all sorts

of other matter printed on each page!). These latter are my version of the

Scanner Daybooks, but far from looking like a beautiful souvenir, they are full

of dense scribbling that I myself sometimees

find it difficult to decipher!

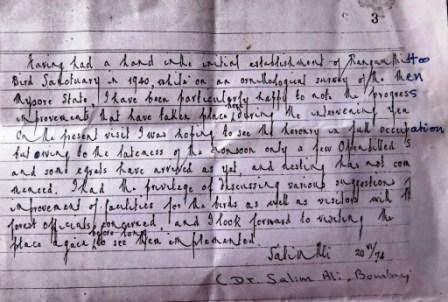

I have seen two examples of the beautiful life-time records

that Sher is apparently thinking of. One is the field notebooks of the famous

Indian bird specialist (ornithologist), Salim Ali: he has recorded each day’s

notes in a beautiful handwriting, complete with drawings and other stuff. I

guess they are preserveed in the Bombay Natural History Society at Mumbai, but

I saw one sample kept under glass at the Sultanpur bird sanctuary near Delhi many years back. I

haven’t been able to locate any scanned images of his journals, but here’s one,

of his handwritten note at Rangantittoo bird sanctuary near Mysore , Karnataka.

The other example was the field diaries maintained by the

professor heading the Centre for Development Studies, Swansea ,

whose system was even more elaborate. He used to record his notes in two

copies (using pencils!) through a carbon paper, and then he’d tear away the

duplicates and sort and file them classified by topic, while the original would

be stored away obviously in order of date (year and month). So his study would

have these arrays of identical looking diaries, and the loose sheets would have

been filed away in their separate folders, subject-wise.

I never tried to emulate Salim Ali’s system (it was just too

perfect!), but I remember I did foolishly try the good professor’s, but I gave

it up after a few days and reverted to my shabby system of a running entry of

notes on everything (including the daily to-do list!) in a series of

mismatching notebooks and diaries. But at least I have all of them bundled

together somewhere! On occasion, I would type up important bits and print them

out for my files and folders on specific subjects. One suggetion that I have

always used is to collect information on specific topics in big ‘ring-files’ … an essential for any type of research. I also

have this thing about collecting newspaper cuttings (which gives you the uncanny

ability to pull out quotes and allusions from years back!). The accompanying

picture shows how easy it is to get behind in this department!

I tried to work Sher’s Daybook system before writing this

piece – I even dug out a nice artsy-looking old empty diary for the purpose –

but I find that this two-page spread per idea is just too tedious (for me!). So

my Scanner Daybook has degenerated as before into a diary where I can go on

jotting down ideas as they come, and mentally slotting each into its relevant project

slot (one longs for an automated categorizer like Lotus Agenda, a PIM which I

have described in my www.doingtheDewey blog). Then as I get to doing whatever needs to be done in

respect of each item, I can make a note of this ‘action taken’ and cross it

off. Indeed, I find now that this is very similar to the diary I maintain for

my financial activities (investments, major purchases) – while it would be

great to have each item classified under different heads (fixed deposits,

provident funds, savings certificates, furniture purchases, equipment,

vehicles, and so on), what I have learnt is that it is crucial to just make a

single serially numbered entry in the ‘daily’ book, with the date, value, and

date of maturity and expected value wherever appropriate. Then I just have to

scan the list once in a while to tend my garden (or attic) of possessions. As I

convert one thing into another, or throw it away, I cross it off and enter a

reference number for the new thing(s). I am now down (or up!) to the 500’s,

that many transactions having been

recorded over the years!

I tried to work Sher’s Daybook system before writing this

piece – I even dug out a nice artsy-looking old empty diary for the purpose –

but I find that this two-page spread per idea is just too tedious (for me!). So

my Scanner Daybook has degenerated as before into a diary where I can go on

jotting down ideas as they come, and mentally slotting each into its relevant project

slot (one longs for an automated categorizer like Lotus Agenda, a PIM which I

have described in my www.doingtheDewey blog). Then as I get to doing whatever needs to be done in

respect of each item, I can make a note of this ‘action taken’ and cross it

off. Indeed, I find now that this is very similar to the diary I maintain for

my financial activities (investments, major purchases) – while it would be

great to have each item classified under different heads (fixed deposits,

provident funds, savings certificates, furniture purchases, equipment,

vehicles, and so on), what I have learnt is that it is crucial to just make a

single serially numbered entry in the ‘daily’ book, with the date, value, and

date of maturity and expected value wherever appropriate. Then I just have to

scan the list once in a while to tend my garden (or attic) of possessions. As I

convert one thing into another, or throw it away, I cross it off and enter a

reference number for the new thing(s). I am now down (or up!) to the 500’s,

that many transactions having been

recorded over the years!

So the Scanner Daybook in my case is nothing but a daily

Ideas-book. I don’t exactly monitor my ‘projects’ here, but in case some

activity develops further, I use another notebook to record notes, ideas, etc.

regarding that subject. So Music, for example, has its own notebooks,

Photography likewise. But my ‘daybook’ has a jumble of everything. One day I

hope to cross off everything in the older volumes, but till then I realize I

have a ‘Scrabbler’ rather than a ‘Scanner’ daybook!

Another idea that I

really like is to set off specific areas of the house for specific activities

or projects. I think this is more practical than organizing a single daybook

for all projects together. It’s like each hobby has its own corner, like you would have separate sub-directories on a computer, or in real life a books corner (or

room!), a carpentry corner (in the garage), and a garden shed (or box). Sher

suggests making a Life’s Work Bookshelf to display the results of whatever

you’ve done or collected in each field over the years, even if it doesn’t amount

to anything earth-shattering.

Finally, of course, you do need to have some source of

income to support all this happy hunting. The ideal thing, of course, is that

you get paid to do what you love (become a paid travel writer or

resort-reviewer, for instance!), but if it ends up looking too much like work,

you may rebel! So there is the compromise of a ‘good enough’ job to keep you

going. In my case, I was lucky to ‘stumble upon’ a profession that has a lot of

in-built variety (the forest service), so I think I had no qualms about sticking

to it for 38 years in a most un-Scanner manner, while I developed various

interests on the side!

I’ll describe the other book, by Lobenstine, next post.

Books cited

Lobenstine, Margaret. 2006. The Renaissance Soul. Life Design for People with Too Many Passions to

Pick Just One. Broadway Books, New

York .

Sher, Barbara. 2006. What

Do I Do When I Want To Do Everything? A Leading Life Coach’s Guide to Creating

a Life You’ll Love. Rodale International Ltd., London .